Hiring new employees can sometimes feel like a high-stakes game of chance. You screen a resume, conduct an interview, follow up on a few references… and hope for the best.

But there are ways to better predict job success—and they’re not necessarily complicated. In addition to the resume, interview, and references you usually include as part of the hiring process, you just need to include a few more objective data points for consideration.

Here are a few of the data points we recommend collecting during the hiring process:

Cognitive assessments

Cognitive assessments help you gauge an individual’s capacity to learn quickly, grasp new concepts, adapt to changing circumstances, and understand complexity in the workplace. It’s empirically the best standalone predictor of training success and job performance.

Not every job will warrant a specific cognitive target. The cognitive requirements for a role will depend on the needs of the organization, and the needs of the role. For example, an organization that occupies a rapidly changing industry—such as information technology—may require candidates with higher cognitive ability. This is because employees will need to keep up with changing market trends and technologies, and process new information at a rapid pace. On the other hand, a role in an industry that doesn’t experience as much disruption might have a lower cognitive threshold. Positions that have a greater deal of complexity—including leadership positions—often require higher cognitive ability.

The PI solution allows you to set a cognitive benchmark, candidate results, and measure candidates’ cognitive ability relative to the role itself.

Other resources that might interest you:

- Smart hiring: Don’t make a hasty decision to fill an empty seat.

- 4 common hiring mistakes ruining your recruitment process

- 8 hiring process steps we recommend (and model at PI)

Behavioral assessments

Behavioral assessments—such as the PI Behavioral Assessment™—help you identify what drives employees at work. The results of these assessments can help you determine if a candidate is the right behavioral match for a role, or if they’ll struggle to adjust and succeed.

Think of it like this: If you’re a right-handed person, it’s easiest to write with your right hand. But what if someone asked you to write with your left? While you could learn to do it, it would feel unnatural. It’s often the same with behavioral misfits at work. While an employee might be able to accomplish their responsibilities in a role, it might be a stretch for them, and disengagement often follows.

Although personality and behavioral assessments aren’t quite as predictive of job performance as cognitive assessments, they can help predict other important behaviorally driven measures that affect culture, engagement, morale, and productivity at a company.

For example, knowing people’s behavioral drives can inform management strategies. The 2021 People Management Report found that managers who use behavioral assessments with their teams are better connected with their direct reports. These behavioral insights allow managers to tailor their leadership and communication style to fit the needs of their employees.

Similarly, knowledge of behavioral drives can support and improve team dynamics. Every time a new hire is made, a new team is formed. Knowing how a new hire will fit into—and change—the existing team dynamic can help you make better hiring decisions.

Evaluating resumes and education backgrounds

If you’ve ever spent hours sorting through endless applicant resumes, take note: Not all parts of the resume will help you predict a candidate’s future job performance.

For instance, you may look to someone’s education first, but there’s little to no relationship between years of education and on-the-job performance. Research has shown that, when combined with cognitive ability, years of education only adds a 1% gain in validity of predicting on-the-job performance. This is largely because many candidates for a given position will have similar levels of education.

Job experience is a little stronger predictor than education, but it’s mostly useful for differentiating between people who are early in their careers. According to researcher Frank L. Schmidt, combining cognitive ability with years of job experience can account for about a 5% gain in validity. But Schmidt also explained that job experience is a useful predictor for people who have fewer than five years of experience. After five years, the amount of job experience no longer serves as a useful predictor of job performance. Schmidt hypothesizes this is because, after five years, a person’s job knowledge cannot increase at a high rate.

Don’t skip the resume screening process entirely. Instead, focus on the areas that matter the most to the job at hand. Try these tips from the Society of Human Resource Management. They explore some great strategies you can use in the process.

A good education does not equal a good employee; so why are employers so often focused on it?

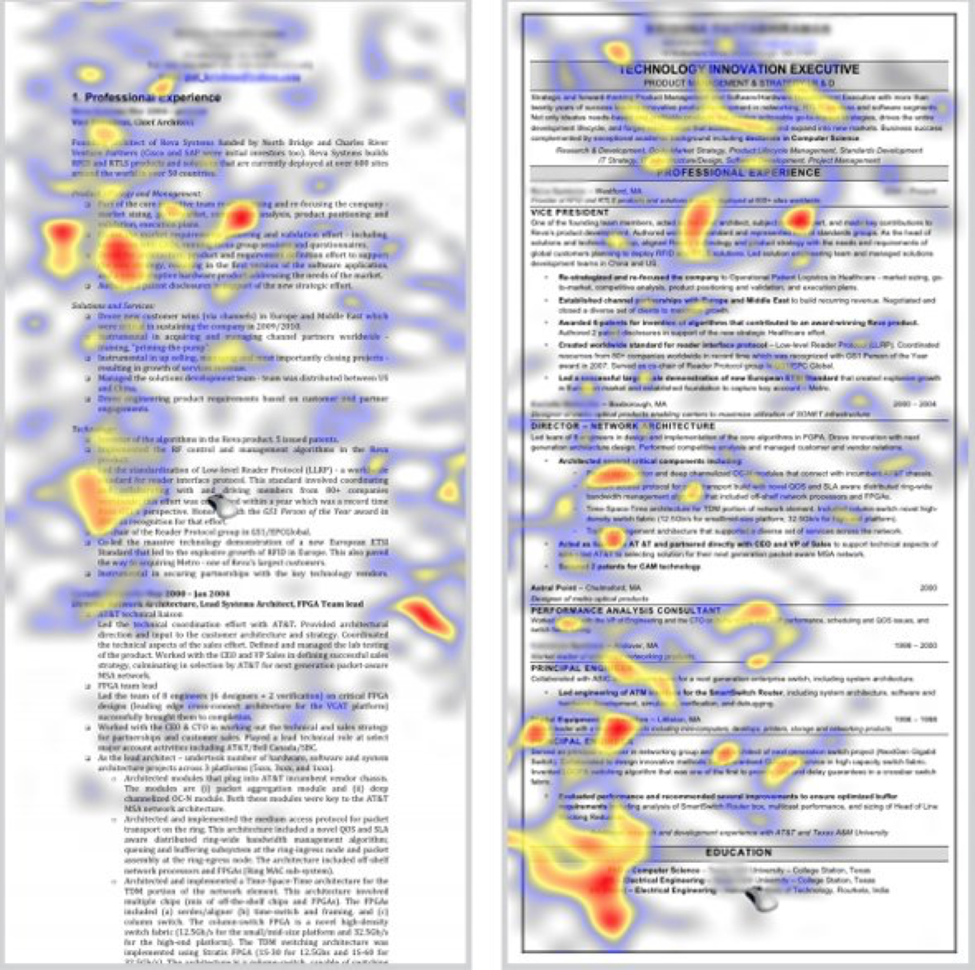

Interestingly, when we do the standard six-second resume scan, a common area of focus is education. See the heat map image below, which tracks the eye movements of hiring managers and recruiters when reviewing a resume.

Notice the heavy emphasis at the bottom of this heat map under the “education” section. The fact that our eyes tend to focus on education speaks to our belief that one’s education is helpful in determining job performance.

Obviously, we assume there’s a correlation between education and work (i.e., good education = good work). The reality is that this belief is more cultural conditioning than anything else. We’ve been told if a candidate graduated from an accredited institution, they’ll perform well.

But there’s so much more to on-the-job success than academic pedigree. Your company has its own unique mission and culture, and within that company exist unique teams with their own dynamics, and specific roles requiring varying behavioral makeups.

Interviews

There’s still debate over how useful interviews actually are. Although Schmidt found that three different types of interviews (structured, unstructured, and phone-based) account for 18%, 13%, and 9%, respectively, in predicting job performance differences, other research—such as this Wired study—found no significant relationship between the two measures.

It’s advisable to use multiple interviews, in varying formats, to really get a feel for the person you’re considering hiring.

You might consider conducting group interviews, or scenario-based evaluations, to assess a candidate’s fit for a given role. Culture interviews, which focus less on a person’s ability to perform specific duties, and more on their morals and principles, can also be telling. You want to hire someone who brings more than just the requisite skill set. Ideally, you add a person who not only fits the existing culture, but who can help it grow and evolve as they do.

Interviewing with the long term in mind isn’t easy, but it will help your team’s chances of not only hiring, but retaining, top-tier talent.

A better way to predict candidate success

Rather than adhere to the false assumption that education is a great predictor of job performance, we can get a much clearer idea about candidate’s likelihood to excel in their job with what psychologists call “General Cognitive Ability” (CGA). It’s also known simply as “g”. Cognitive ability can be measured, and thus it can provide predictive ability. In fact, “g” is considered by many IO psychologists to be the single best predictor of job performance.

The very thing many hiring managers focus on the most—education—is often a poor predictor of success. A much smarter way of evaluating candidates is to assess their behavioral drives and cognitive ability.

Collect a variety of data points.

When it comes down to it, there’s no one predictor that can tell you who would be the best hire. As predictive as cognitive and behavioral assessments are, they don’t paint the whole picture of who someone is—and neither does a resume or an interview. Instead, focus on combining as many of these elements as you can. Other, more job-specific measures—such as skills assessments and culture interviews—can help as well. The more measures you use in the hiring process, the better your odds are of predicting performance and making your next great hire.